John Newmark Levi Sr.

WESTERN STATES JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

October 1971: Volume 4, Number 1

Contributor………

John Newmark Levi Sr., B.A.-----Mr. Levi is a fourth generation Los Angeleno, a great-grandson of the famous Harris Newmark. His grandmother was born in Los Angeles in 1881. Mr. Levi is an industrial executive with a firm that has been owned by his family for almost ninety years. He is a graduate of Stanford University where he was an Economics and Journalism major and Editor of The Stanford Daily. Mr. Levi’s wife Aimee Nordlinger is a descendant of the pioneer Los Angeles families, the Nortons and the Nordlingers.

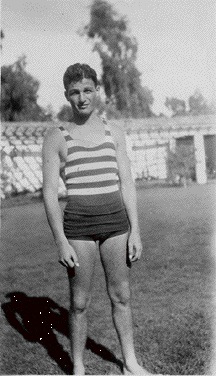

John N. Levi Sr. 21yrs. In 1926 at Standford University

THIS IS THE WAY WE USED TO LIVE

By John Newmark Levi, Sr.

Edited by William M. Kramer

Editor’s Note

This is an informal social history of the life of Los Angeles Jewry’s first families during the early years of the twentieth century. The account is edited from eight hours of oral history tapes and interview notes. It has undergone revision by author and editor in order to add identifications of persons and places. It indicates the modes, moods and manners of the second and third generation of well-to-do Los Angeles Jewish families, whose progenitors had reached the city in the nineteenth century. The editor wishes to express his appreciation for the use of interview tapes that were made by one of the students at San Fernando Valley State College, Mr. Paul Rosenberg.

John Newmark Levi, Sr., (b. 1905), is a corporate executive who, with his partner, Stephen N. Loew, Sr., (b. 1891), gives leadership to the pioneer Los Angeles firm, Capitol Milling Company, purchased by Loew’s father, Jacob Loew, (b. 1847 in Germany), in 1883. Jacob Loew came to the United States in 1865 and to California in 1868. Mr. Levi’s parents were Herman Levi and Rose Loeb Levi. His father was born in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1870 and came to the United States to live with relatives in Quincy, Illinois, when he was twelve. He was brought to Los Angeles in 1891 by Jacob Loew, his uncle. Herman Levi was later president of the Capitol Milling Company. Jacob Loew had married Emily Newmark, a daughter of Harris Newmark, in 1885.

John N. Levi’s mother Rose, (called “Schatzie,” b. 1881) above at 20 wearing an engagement dress that she also wore for a reception for President and Mrs. McKinley in 1901, was the daughter of Leon Loeb (b.1845) and Estelle Newmark Loeb. Loeb was the successor to Eugene Meyer, his first cousin, as French Consul in Los Angeles and he was one of the owners of the City of Paris store, located on Spring Street, near Temple. He was decorated by the French government but resigned his consulship as a protest of the Dreyfus affair. Loeb was an 1866 Los Angeles arrival. He had been born in Strasbourg, France. His sons, Joseph P. And Edwin J. Loeb created a major law firm in the West.

Newmark Loeb, John Levi’s grandmother, was Harris Newmark’s eldest daughter. She had been born in Los Angeles in 1861. Her mother, Sarah, (b. 1841), was a first cousin of Harris Newmark, whom she married in 1858. Sarah’s father was Joseph Newmark, who became the lay rabbi of Los Angeles when he arrived in 1854.

Aimee, Mrs. John N. Levi, Sr., is the daughter of Louis F. Nordlinger and Esther Norton Nordlinger. There are close family ties between the Nortons, Nordlingers, Levis and Newmarks over the generations. John Levi has a sister, Elizabeth (Mrs. Louis Lissner), and two brothes Richard and Leon. John and Aimee Levi have two children, Linda and John Newmark Levi, Jr. -- W.M.K.

This is the way we used to live in Los Angeles from about 1910 to 1920. Our group consisted of the families and connections of the Jewish pioneers who came to the community in the early part of the secons half of the nineteenth century. What I’m revealing is typical of our well-to-do class. We were all cousins or close friends with cousins in common, or we were closer than that. We were a regular part of the community as well as a special part of it. We got along with everybody.

Home life in the old days was certainly different than it is now. Our family resident was at 929 South Lake Street. The three-story structure is still there. It was really nothing much at all, sort of a cracker box on about a fifty-foot lot. If you were to look at it today you might think that four people, not more, would be comfortable there. In those days we were three children plus my mother and father. And then we had a lot of help. Marie Sturdevant was the nurse-governess who played a big part in raising us. We had an upstairs maid who doubled as a waitress, that was our Katie. Of course, there was also a full-time cook. That was the regular household except for my cousin, Fritz Eisenan, who came over from Germany to live with us. We all had separate beds. Where we all found room, I don’t know. This was the occupancy of our house.

If anybody were sick, there would be a trained nurse who would be staying with us, too. Besides those who lived in the house we used to have a seamstress who came to us, a Mrs. Nicholson, of Pasadena. She made much of my mother’s clothes, and she was there one or two days a week. We had a Miss Bessie Leach, who just did mending. She came once a week. We had a laundress who came three days a week to do the washing for the family.

We also had a woman who came and washed our hair. All she did was shampoo the hair of the family. My sister had a piano teacher who came to the house. My brother had Herr Werner, who taught him violin and German. Herr Werner’s sister, Fraulein Werner, also came once a week and gave us German lessons. Home waslike Grand Central Station.

The total salary probably came to a few hundred dollars a month, because help cost nothing. I remember Mr. Barnhardt, who was our cabinetmaker. He was a handyman, plus. He was fantastic! The man did the most beautiful work you’ve ever seen. He was at our place at least once a week fixing things and doing odd jobs. Mr. Bernhardt worked for us and about ten other households of our family. They kept him busy because he was first class. He made the most beautiful furniture, too.

It seems funny when I tell people of this parade of help that came into our hours regularly, but there were more. I can remember when we were sick and had to stay home from school, my mother would have a private teacher come in to bring us up-to-date on our class work, so that when we went back to school we’d be up with the others. We lived the way you see in those old movies with all the help, with the upstairs maid, the parlor maid, and all that sort of thing. It was just part of our life.

Many of the help, the cooks mostly, were Irish or German. They were all very carefully supervised by the housewives, who were good cooks and could tell them what to do. My mother, however, could never cook, but she was a good supervisor.

Dad a few months old, Schatzie (25 yrs.), and Aunt Elizabeth Levi Lissner (4yrs.) 1906

I never had any musical talent at all. I don’t know if there were any particularly gifted ones among the kids we knew, but they were made to learn and most of them took private lessons. Aimee, my wife, took piano lessons as a little girl. She took from a very fine teacher, Herr Thilo Becker, who was one of the best in Los Angeles. A brother of mine took violin lessons for several years, but he was a squeaker. He didn’t have much talent, but he liked it. I don’t think there was a good musician in the whole Newmark family. I think it was kind of a negative trait; many of us were tone deaf, including myself. Harris Newmark shipped a grand piano around the horn, one of the first in these parts, but I don’t think anyone could play it. It was just good decoration.

There was a nice social life here, relaxed and comfortable, much more so than now. We were aware of the social graces. I wouldn’t say that our Jewish families were high society, but we were nice society. Our people were well respected and regarded. But it was a small city then, and we were a small Jewish community.

My great-grandfather Harris Newmark moved away from Los Angeles in the 1860’s and went to New York. But he was drawn back here again. He was getting out of a dusty, little backwoods town, which he had come to in order to make money, but he didn’t think it was the place in which to raise children. New York, he felt, was a more proper place for his family to grow up in, because it had more cultural opportunities. But he only stayed away about a year-and-a-half, because life had a good quality in California. So, after he had bought a house in the East and settled down there, he packed up and moved back here again.

Family life was much more important in the old days. We saw a lot more of the family then, than we do now. We all lived in close proximity. For example, when we lived on Lake Street, great-grandfather Harris lived on Westlake, two blocks from us. My great aunt, Mrs. Jacob Loew, lived on Alvarado. My great uncle, Maurice H. Newmark, lived on Beacon Street. My great aunts, Clara Kingsbaker (the widow of Moses) and Rosa Jacoby (the widow of Morris), also lived on Lake Street. They were sisters of Jacob Loew, my father’s uncle.

Another one of the family, Louis S. Nordlinger, a double cousin and a cousin to my wife as well, lived on Ninth Street around Union. It seems that the whole family lived within walking distance, perhaps no more than six or seven blocks. Most of the kids we went to public school or Sunday school with lived within an area of probably ten or twelve square blocks.

I can still remember, on a summer evening after dinner, my dad, Herman, would say to mother, “Schatzie, come on, let’s walk over to aunt so-and-so’s.” So the three of us kids and our folks would go over and we’d sit on the front porch of somebody’s house. There would be other kids there, and we’d either talk or play games.

There was a lot of card playing between the men at night. My great-grandfather, Harris Newmark, would want to have a game, and the men would go over to his house. They would play cards with him in the upstairs sitting room for a couple of hours, and the women would sit downstairs on the porch or in the living room.

Up until 1915, when I was ten years old, we all lived close to one another. Later on, when we moved further west, we were more scattered, but the family still kept together. On Tuesday nights, we would meet at one of the aunts. And then, on another night, we’d probably go to somebody else’s house. There was great personal contact.

Social life was mostly talking and card playing. The men usually played cards and the women talked and sewed, and theyoungsters who went along would talk and play games, nothing exciting. When we started studying and getting assignments at school, we didn’t participate so much in the evening things.

The summers were unbearable in Los Angeles, so we would go out to the ocean. Originally we would summer at Venice and later on at Ocean Park. In May, my mother would go down to the beach to rent a house for the hot weather season. I never remember staying in town all summer until I was eleven or twelve years old. Los Angeles was a hot and dusty place. Few streets were surfaced and water wagons were used to help keep the dust down. Except for a few places, the area from Vermont Avenue to the ocean was all open fields. If you could afford it, summertime was the time to go to the beach.

The Harris Newmark family had a second home in Santa Monica (1311 Ocean Avenue) and there were always relatives close by in Venice, Ocean Park and Santa Monica, so that we could spend our evenings together. It was the same in the summer as it was in the winter. It was almost a ritual.

After supper we would all walk to somebody’s house and sit around on the porch, or maybe we would take a stroll on the boardwalk for a while and then come back and sit. The boys and girls usually went along. Of course, we weren’t allowed to stay up too late. In those days we stayed up until nine or nine-thirty.

The Kasper Cohn family (he was the banker) had a beautiful place that they rented every summer on Sunset Avenue, right on the boardwalk, in Venice. They had a big glassed-in porch; it seemed tremendous at the time. That was one of the places where the family used to gather. We lived one block further down, on Breeze Avenue at one time and then at another place on Wavecrest. Everybody would walk down to Kasper Cohn’s house after dinner and meet there.

The families kept in touch all year long. The whole Solomon Lazard family lived near what is now Wilshire and Westlake Avenue, where the medical buildings are. They had about four houses together, only three blocks from where we lived, and I can remember walking over and meeting the other youngsters. The Lewin and Lazard families were of the branch that came from Solomon Lazard, who married my great-great-aunt, Caroline Newmark. We had a very closely-knit Jewish community then.

We went with many gentiles, but we always had our Jewish friends whom we fell back on. Most of our contacts were Jewish. My father did belong to the Los Angeles Athletic Club. They did have some Jewish members and a few of the charter members were Jewish. I went there as a boy and used the swimming pool and the gymnasium, but the membership was, I’d say, about ninety-five percent gentile. It so happened that the young Jews who did belong were my close friends. But the country clubs around here accepted very few Jews. In fact, the Hillcrest Country Club was started by two or three Jews, one a Newmark, who had belonged to the San Gabriel Country Club and had some sort of unpleasantness there. They saw the importance of starting a Jewish country club, and once they did, they resigned from San Gabriel.

Families were probably happier if you didn’t intermarry. And most of my friends did marry in our religion. It wasn’t so very true later. Actually, our parents always expected that we would marry within the faith. Still, I don’t think that after World War 1 they would not have minded too much if we hadn’t. They were rather liberal and in California we weren’t so bound by tradition. There wasn’t too much thought when we were young about dating non-Jewish girls. When we did, their parents never said anything, but you had the feeling that they would have been happier if their daughters didn’t date Jewish boys seriously. We Jews knew that we weren’t going to be invited to the Junior Cotillions, which was a big, gentile social event. For that matter, we never expected to be invited to join the high school fraternities, and we weren’t. We had some things of our own.

All the little Jewish boys and girls had to go to dancing school downtown. Every Saturday afternoon we were off to Kramer’s Dancing Academy (Henry J. Kramer, 932 South Grand Avenue). The girls sat on benches around the wall. The boys learned how to bow and ask the girls, “May I have this dance with you?” We learned the polka and the waltz. It was the most God-awful thing. We had to wear stiff Eton collars that pinched into your neck. Black ties were required and we wore dark blue serge suits with long stockings. The boys detested going there. I don’t know how the girls felt about it.

My folks made me go for a couple of years. I can still remember what it felt like when when I was about eight years old. I would throw myself on the floor, kicking and screaming that I wasn’t going to go to the dancing school. Fortunately, I had a nice great-uncle, Jacob Loew, who came to my rescue. He offered to take me fishing on Saturdays and that was the end of that. No, I’ll never forget going to Kramer’s. We weren’t allowed to cut across the floor to ask a girl to dance. We were supposed to walk around the sides like little gentlemen. To torment Mr. Kramer, we boys would tear across the floor.

Later on, when we were older, we had social dances at various homes. I remember the dance programs that our dates had. Each dance was numbered and there was a place in the program for the boys to sign in. The programs were fancy, with little ribbons and pencils. If your date was popular, you were lucky to have a dance with her yourself; if she wasn’t, it was pretty sad. Since, by in large, the gentile social events were not for us, we had a Jewish Cotillion at the Hollywood Women’s Club weekly or fortnightly. I was fourteen or fifteen then. Later we graduated to the Cocoanut Grove. It had a fifty-cover charge then!

The young Jewish blades of the generation before ours made the Vernon Country Club their headquarters, as later we made the Grove and Biltmore ours. The club in Vernon was somewhat notorious. They had liquor, some good bands, and the place lasted until prohibition.

Much of our social life revolved around our public school and Sunday school, friends. Most of them went to a very few schools and only the one congregation. I attended Hoover Street School, then Berendo. Our group also went to Virgil and then practically all of us went to Los Angeles High.

In my boyhood days the Jewish community was just one set as far as we knew. They were mostly German Jews, but probably only a generation or two out of Poland. They had, however, picked up a good German background. It was the same way with our connections in San Francisco. Of course, there were some French Jews aswell. The Russian and Eastern European Jewish immigration that was to contribute so much to our local Jewry didn’t make an impact until later. The Jews we knew belonged to the Concordia Club. They never thought of it as something very exclusive because everybody they knew in the Jewish community was in it. This was when I was very young and I remember that it disbanded, with most of the people surfacing later in the Hillcrest Country Club.

The Concordia Club was located at Sixteenth and Figueroa Streets. Sixteenth is now Venice Boulevard. It was part of a very fine residential district at the time it was built. The Concordia building was made of white clapboard, rather an imposing structure for those days. It was a Jewish social club. While it was a men’s club, they did have family affairs and functions. They also had dances and events for children. I can remember the Purim plays and the grand march at the dances. It was a social club with much card playing. My father played poker there. They had a bar and served food. In the evenings excellent sandwiches were served. The wives, my mother included, would ask the men to bring sandwiches home after the poker games broke up.

After the Concordia Club closed down, a group of men older than my father used to meet at the home of one of the ex-employees of the club, in order to keep the game going. He gave them a place to play cards, usually poker, and fixed them up with food. That group kept the game going for fifteen or twenty years after the Concordia ceased to exist. These men included James Hellman, Herman Goldschmidt, Berthold Baruch and perhaps five others.

Another gathering place in the early years was Al Levy’s Restaurant (Third and Main Streets). When I got to know Al Levy, he was a little old man. He started out with an oyster cocktail wagon. He eventually had a very beautiful restaurant, which was the place to go. He was a friend of the family although no relative, despite the fact that in Germany our family had used the “Levy” spelling.

Our group also favored another restaurant called Marcell’s. It was located on Third between Spring and Broadway, upstairs. Later it moved to Eighth between Broadway and Hill, on the north side of the street. Harris Newmark owned the property.

Some of the older group enjoyed horseracing and Santa Anita until gambling became illegal. “Lucky” Baldwin had acquired land there from the Newmarks. There were also sulky races in Exposition Park that some of the families enjoyed. A few of the Jews went to cockfights with the Basques. Jews and Basques knew each other from the early period when Jewish merchants became bankers by holding the money for Basque sheepherders and giving them credit.

Much of our social life revolved around resorts. The Southern Pacific or Santa Fe railroad lines ran many of these resorts and their hotels. The business was profitable and it generated traffic for the railroads. As youngsters, we children were taken along to places like The Coronado Hotel, the Del Mar Inn, the Potter in Santa Barbara and the Del Monte near Monterey. I think that these were big wooden hotels. Many Jews visited these places but they weren’t Jewish resorts or hotels such as you find today in the Catskills or Miami Beach.

My parents loved to go to San Francisco. When the roads were good they would take the car, otherwise they would go by train. It was generally agreed that social life was gayer up there, where we all had friends and family. Closer to home, we enjoyed the Crystal Pier with Nat Goodwin’s Restaurant at Ocean Park. Goodwin was an actor; later his place became the Sunset Inn. For myself, I loved to go to the salt-water plunges that were our swimming holes near the ocean. I was a good swimmer and did very well in water sports, achieving recognition in High School and College.

Automobiles were a big thing in our lives when I was very young. Almost as soon as we got a car, my mother hired a chauffeur. From about 1912 she had her personal car an Abbot-Detroit. We had no driveway at our house, but there was an alley in back that lead to the garage where the cars could be parked. My folks let me drive when I was twelve, but they wouldn’t let me have the car alone until I was fourteen.

We frequently went driving on Sunday afternoons. Picnics on Sunday were common when people began to use automobiles. When I was five years old (1910), nearly all our family and friends had autos. You rarely went by yourself in a car. Usually, two or three families joined together to go on a Sunday afternoon drive. This was partly because if you had tire or some other trouble, there would be someone to help you. There were no service stations. We had a gasoline tank in our backyard. It was surprising how often a tire would have to be changed. In those days you didn’t change a tire like you do now. You had to make your own puncture patches. Our parents had little vulcanizing outfits that they would take with us on the family outings. Since the roads weren’t very good, there was always a real danger of getting stuck in the mud. When that happened, everybody got out and pushed shoulder to shoulder.

My father’s first car was in 1907 and was a Duro automobile. It was a Los Angeles brand, as I recall. The great-grandparents had a Pierce Arrow. My great-uncle, Marco Newmark, had a Stanley Steamer. My wife’s family, the Nordlingers, had a Pathfinder. We would take the cars out on picnics to places like the Arroyo Seco, always carrying a big lunch that the maids had prepared. It was always quite a trek. I loved to go to Azusa, where you could get the most wonderful tamales at a place that should have been closed up as a health hazard. Azusa was a very long trip and pretty rough traveling. You had to cross the San Gabriel River. Some of the time the bridge was in a poor condition, but in the summertime there wasn’t too much water, so when you had to, you could ford the river.

I still remember one big picnic. Just as we were starting out it began to rain. So instead of driving out into the country, we all went over to Sam Behrendt’s backyard. He was a very close friend. His son George was one of my contemporaries. Everybody pitched in and dug a pit in the yard and a grill was put over it for cooking, after it was filled with wood or coals. Everything tasted good and that was probably my first California barbecue.

I don’t think of our own part of the family as being very religious. We knew we were Jews, we had our obligations, and we went with Jews. I remember that I didn’t know anything about Bar Mitzvah. My brother Leon and I went to Congregation B’nai B’rith, but we were never confirmed, although my sister Elizabeth was. We didn’t know about yarmulkes. Now we know about these things. We also didn’t know about funerals, because children weren’t required to go. I remember when people died, like my great-grandparents, but we children were kept away from things like that, and I still think this is right.

My mother was president of the Sisterhood at the Temple and even when she got interested in Christian Science, she stayed on as president of the Temple Ladies’ Sewing Group. My mother was interested in metaphysical religion and she used to discuss things with Rabbi Edgar Magnin. She was a student of the Bible.

My father came over from Germany as a half-orphan, with an orthodox grandfather. His own father had died and his mother remained overseas. He had all the things like a tallis and tefilin. He had so much that he turned away from it all, the rituals of orthodoxy. I don’t think he ever entered the Temple, though, he would drop us off atthe door. He did keep up his membership, however, because he thought it was the right thing to support the Temple. He was really anti-religious because of the wrong kind of orthodoxy in his youth.

The only Jewish wedding that I have a recollection of attending as a boy was when I was eight years old. It was the wedding (1913) of my present senior partner, Stephen Loew, who was my father’s first cousin. Loew was married at the Alexandria Hotel. His wife’s name was Lucille, and she was a Polaski, the daughter of Isador and sister of Arthur and Louis. They were an early family here in Southern California. The wedding was very, very plush. It was an evening, dinner affair, and we went to watch the ceremony and then our nurse shepherded us out. It was a beautiful wedding with all the formalities; a very elegant social wedding. Dr. Sigmund Hecht, of Congregation B’nai B’rith, officiated.

Engagements weren’t very long in those days. They usually lasted two to four months. Most of the young people who became engaged knew each other for a long time. There were not many big surprises when the traditional diamond was given. We were all of the same social group, with the same background for the most part. Girls began going out when they were about fourteen or fifteen. At least they tried to get out then. Their parents would try to keep them in until they were about sixteen years old. Boys went out at sixteen.

A boy wouldn’t have to go to the girl’s parents and ask if he could take her out; the girl would ask if she could go out. There weren’t any problems because the families were close and everyone knew each other. Because of this relationship between families, the parents didn’t have to worry about whom their daughter, or son, for that matter, was dating. There wasn’t much conscious matchmaking, at least no more than there is today. You were just thrown together. You saw each other because your families knew each other.

We had many gentile friends, but as we got older we associated more with our Jewish crowd. Even those that intermarried – their wives would seem to become more Jewish than the others. As you matured, you realized that you had more in common with Jews. When you are young your good friends are your party friends, but many of these friendships did not have any real foundation. You don’t have religion or a way of life in common. We didn’t know the Jews from Boyle Heights, who came later, until we grew up. But now our friends are from the whole Jewish community.

Many of the local Jewish boys served in World War l. The fact that many had a German background didn’t cause them to be inconvenienced or accused of disloyalty. Up until the war, there was some pro-German sentiment. I can remember, however, that my father was fiercely anti-Prussian. In 1914, Harris Newmark wanted the Germans to win, but as my mother told me, “He choked on the dose.” He, like all of us, became anti-German after learning about the atrocities of the Germans against Belgians. I can still recall the boys four or five years older than I, who were going off “to do their bit.” My sister Elizabeth was closer to that age group and she was very war conscious. At Temple B’nai B’rith, our families and all the others were busy rolling bandages.

Besides the war, the other big event I can think of during my childhood was a trip to Europe. Our families often went to Europe for extended stays to visit relatives, or for the grand tour or other cultural, educational, or health reasons. We went for six months in 1912. On the trip were we three children, in the charge of our governess, Marie, my parents and my mother’s mother, Estelle Newmark Loeb. The main reason we went was to see father’s mother in Stuttgart, but we also spent time in Lucerne, London and Paris. When we were enroute, the word came to our ship that the Titanic had sunk. It was very frightening to us as children, since we had also sighted icebergs and were aboard ship. We traveled on German vessels in 1912, and I can remember on the return trip there were many of our brother Jews from Poland and Russia coming steerage to the United States, for freedom and opportunity, as our families had earlier. Part of the time on the trip we were with the Alexander Meyer family. They had two boys, Myron and Andrew. Alexander was a brother of Ben Meyer, the banker.

In the period from my birth in 1905 to about 1920, Los Angeles Jewry, as I knew it firsthand and from family memories, was a very warm, comfortable and prosperous big family made up of blood relatives, marriage ties and close friends. In my childhood, we were all one. You seldom met any new people, unless they were connections from San Francisco or back east. Up until about 1920, we were very in-bred.

Though we were a Jewish group that supported Jewish institutions, we seemed to be getting away from Judaism, yet we stayed close to Jews. But, when I look at what is happening now, the pendulum has swung again and the children are back in Sunday school. They attend the new congregations and, of course, the old, congregation B’nai B’rith’s Wilshire Boulevard Temple. The Los Angeles Jewish community’s spiritual founders in the mid-nineteenth century started something good that is alive and well.